Long, digressive, funny and deeply moving, Elvis Costello’s stunning memoir is a sort of biography of popular music itself.

I still remember the day – it was 15 March 1986, an unusually warm early spring Saturday – when I walked into an Our Price record shop and saw that cover for the first time: a scruffily bearded man wearing a country and western shirt and a replica of the Imperial State Crown. The sleeve simply said “King of America” but Our Price had helpfully put a sticker on the front: “The New LP from Elvis Costello: PLAY LOUD”. I did – more times than anyone around me will care to remember. But we all grew to love that record. Even my Dad liked it.

I already had a few Costello LPs – including his previous, slightly dodgy outing Goodbye Cruel World (1984) – but this was the moment I became a diehard fan. At some point I acquired a cassette of King of America (no idea why – I never bought tapes) and some time in the 90s I bought a CD version too. I still have all three copies.

Mere months later, in September I think, another astonishing Costello LP appeared. Blood and Chocolate was recorded, unlike King of America, with his old band, the Attractions. Although they were very different records, I’ve always seen them as a pair. Not a day goes by without me singing at least one of these 26 songs in the shower or humming them as I walk down the street. Even today, songs I’ve heard a thousand times can make my eyes sting. They are the songs I turn to in both my brightest and darkest moments. They are the soundtrack to my life.

Mere months later, in September I think, another astonishing Costello LP appeared. Blood and Chocolate was recorded, unlike King of America, with his old band, the Attractions. Although they were very different records, I’ve always seen them as a pair. Not a day goes by without me singing at least one of these 26 songs in the shower or humming them as I walk down the street. Even today, songs I’ve heard a thousand times can make my eyes sting. They are the songs I turn to in both my brightest and darkest moments. They are the soundtrack to my life.

I had no idea that music was this powerful. That you could almost live inside the world created by a record. And here were two of them in the same year from the same man. To me they’ve become much more than mere recordings. King of America is a road movie, shifting between cheap Nashville motels, Las Vegas cabarets and the stifling streets of New Orleans. Its cast of characters are nightclub singers and impressarios, prostitutes, drunken writers, army vets and unhappy GI brides. Blood and Chocolate is an altogether more claustrophobic affair: a howl of rage from the shut-up bedsits and shattered family homes of England. It contains one of Costello’s classic songs, I Want You, a desperate and dark ballad about sexual obsession and the suppressed anger of loneliness. Costello himself says singing the song night after night was a kind of punishment for all “the cruel and irrational things” he’d done – until he just got used to it. The American music critic Stephen Thomas Erlewine called it “nasty”. It is, but it’s beautiful too. And so truthful, it hurts.

I immediately bought a guitar and tried to write songs. I didn’t get far with that, but I still play, the same guitar, almost as badly as I did in 1986. More importantly, it was these two Costello LPs that made we want to write. I got my calling. I knew I wanted to use words to spark feelings, to paint pictures, to tell stories. Within months, I’d given up my job as an accounts clerk and gone to university, with the intention of becoming a writer. I’ve ended up doing a lot of different things (they call it a “portfolio career” now; I think the old term was “no career”) but I’ve always kept writing.

As a lyricist, Costello has that Joycean knack of making a word or phrase seem to express two or three different things at the same time. His songs can swoop from menace and vitriol to the utmost tenderness in the same verse, with melodies that can both soothe and hurt. It’s odd that anger – such a powerful, ubiquitous emotion – was almost entirely absent from popular music until the mid-70s, and no one does anger in music better than Costello: cutting and witty, often self-deprecating, but also brimming with the guilt and remorse that anger brings on. And anger can be tender too. If you don’t think so, listen to Alison, or Bullets for the New-Born King.

Take this couplet from the song I’ll Wear it Proudly on King of America:

Well, you seem to be shivering, dear, and the room is awfully warm,

In the white and scarlet billows that subside beyond the storm…

I have no idea what that means to Elvis, but there is so much packed in there, it’s hard to know where to begin. There’s tenderness but also a hint of menace. There’s that beautiful (implied) association between the clouds outside and the pillows on the bed, and the reference to the passing storm which metaphorically suggests this is the aftermath of a row. Maybe I’m reading too much into it, but I’ve carried the image of that stifling hotel room – and the loneliness inside it – around in my head for more than half my life.

So, to Unfaithful Music and Disappearing Ink, which is probably quite different from any other musician’s memoir you’ve read. First off, it’s actually written by the musician himself. In prose, Costello has a chatty, digressive style which is a million miles away from the gin-spiked vitriol of his early recordings. His 36 chapters follow a meandering course through his life (and those of his parents and grandparents – sometimes you wonder if he’s been lined up for the next series of Who do you think you are), often veering off in the manner of Montaigne’s essays to talk about whatever takes his fancy before (sometimes) coming back to the point. It’s a bit like being holed up in a pub with Costello for a couple of days or sharing a long train journey with him. But unlike a long pub chat, it all begins to make sense towards the end.

This is also a book about music, rather than rock star excess and battles with drink and drugs (though Costello owns up to a lot of drinking and a fair few “pills”): it’s a book set in recording studios and concert halls rather than mansions and luxury hotels. The extent of Costello’s musical knowledge and influence will knock your socks off; even I had no idea how many pies he’s had his fingers in. To some reviewers this cast of collaborators, friends and other artists seems like namedropping, but almost all of them are people Costello has made music with. What was he supposed to do? Refer to Bob Dylan as “this bloke from Minnesota I met in New York”?

While some reviewers over-concentrated too much on the confessional nature of the book, it wouldn’t be Elvis Costello if there wasn’t plenty of remorse on show, especially over the affairs that led to the break up of his first marriage – to Mary Burgoyne. He makes no excuses for that, or for the “nigger” remark about at Ray Charles during the Attractions first US tour in 1979. Costello describes, in some detail, the stupid and drunk behaviour of a lonely young man in a foreign country, trying to get on in a business where shocking people was de rigeur. Only an idiot could think that Costello — a stalwart of Rock Against Racism — was a racist, and if his apology was good enough for Ray, it’s good enough for me.

No apology is necessary for the nastiness in some of Costello’s lyrics, especially his early stuff. If Elvis’s song-writing has been about anything, it’s confronting the emotions that people really feel, not just the one’s that are laudable or even understandable. Some people are spiteful and young men do rage against women. We all feel bitter and angry from time to time. Holding Costello personally to everything expressed in his lyrics over 40 years is as stupid as attributing to Charles Dickens the violence and misogyny of Bill Sikes or accusing Martin Amis of psychopathy for putting the thoughts of John Self down on paper.

Costello’s father – the big band singer Ross McManus – looms large over the whole story. Without Ross, there would’ve been no Elvis Costello – and not just in the biological sense. Their relationship is the golden thread running through both the book and Elvis’s career itself. All his musical magpie-ism finally makes sense in the context of a shared musical heritage of the McManus family which goes back to the beginning of the 20th century. There are no boundaries in popular music: it certainly didn’t begin in 1976 with punk or in 1954 with rock and roll.

Costello’s current series of “Detour” gigs (apparently – I’m going to see the Paris show next month) feature a selection of Costello classics, music hall and big band songs going back to the 1920s and an miscellany of more recent country and rock and roll covers which change each night. In between, Elvis tells stories and shows video clips from his life and career. Much like these shows, this is not just Costello’s own biography, but a sort of biography of popular music itself.

Passages about Ross’s slow decline and death from Alzheimer’s drift in and out of the story, especially towards the end. They are deeply moving for anyone who has lost a parent, and they also show why Costello is such a great songwriter: whether he’s writing about marital break up, war, unemployment or the loss of a loved one, he sees straight through to the emotional core of the situation.

If you’re already a Costello fan, you will lap this up and wish there were more than 674 pages (and an index!). If you’re not, this is an extended pub conversation with a real musician who knows everybody and has done everything. If you also buy the accompanying soundtrack LP, you might just see what I’m getting at.

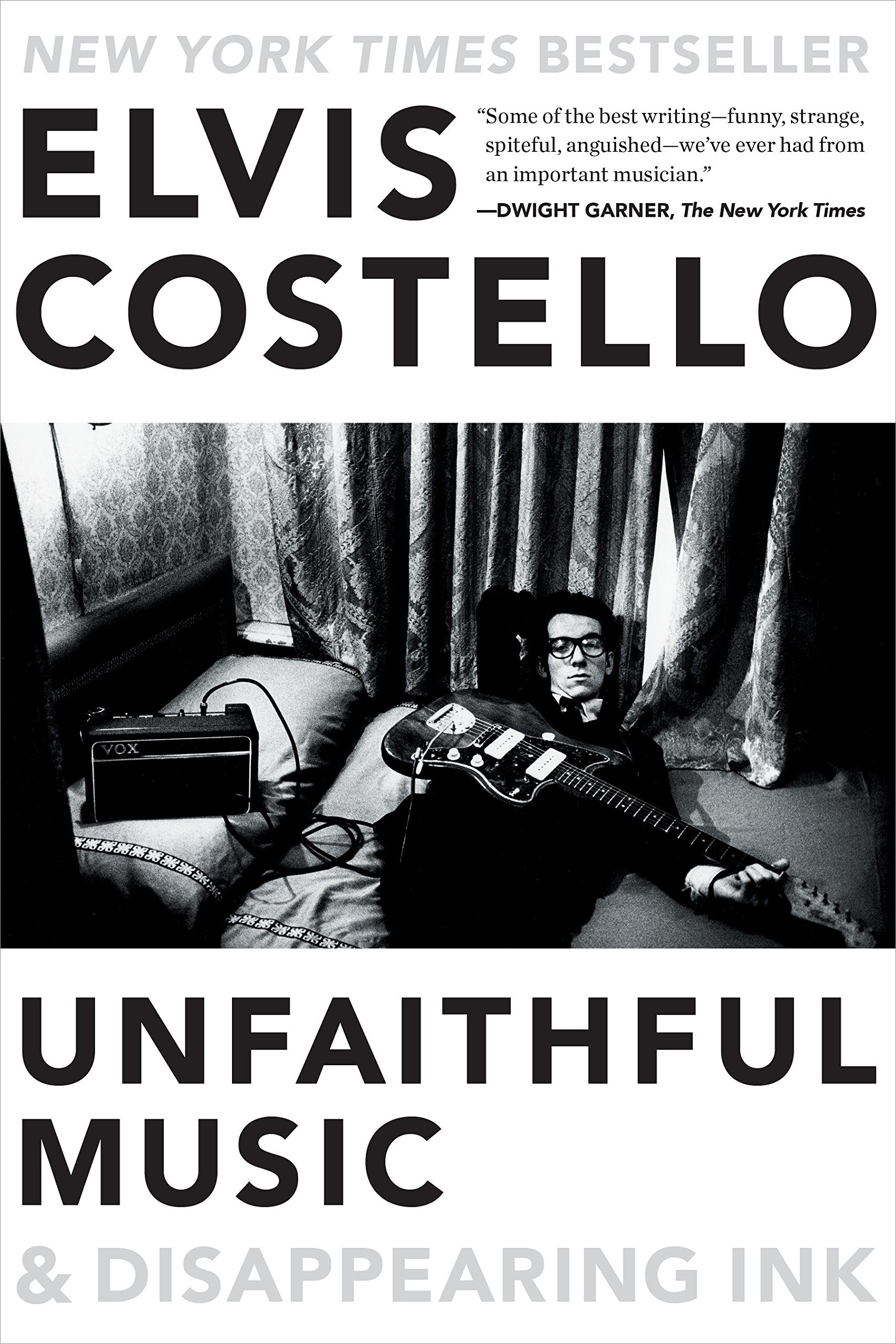

Photo: Elvis Costello at the Roundhouse. © 2016 Craig Ryan